Patan Museum

Patan Museum is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and the former royal residence of the Malla dynasty between 14th and 18th centuries. It sits amidst Newa-style temples in a section of the Royal Palace at Patan Durbar Square, a portion of which served as a prison until 1990 CE. Kathmandu Triennale 2077 presents here a conversation, built on both confrontation and harmony, between different lineages of artistic grammar; from paubha painting and East Asian ink, to amulet making and hair braiding around the world. These lineages intersect and synchronise in our time as contemporary forms of artistic expression, some against the odds of history, vibrantly making sense of fractures, multiplicities, and common stages. But the exhibition here is also looking beyond the dominant traditions of the contexts it brings, showcasing practices from communities that have often been subjected to processes of internal colonisation by their own, often post-colonial, state and its official cultural narratives, with a particular focus on Nepal.

As you enter the different spaces of the museum and the neighbouring spaces at Bahadur Shah Baithak, you will encounter artworks that connect our bodies, their insides, the networked maps of our social worlds, and the cosmos with its frightening designs. You will see artists who have worked in different traditions, whether thangka or pandanus, yet all of them are of our time. Many of the artists harness the power of women to think about our world. As you enter one of the corridors, artists speak from the (gendered) body – its microscopic interiors, its laterals in the social crust of the Earth and its higher place in the universe – with each level populated by strangers and dangers, as seen through different traditions of healing and art. The highest level of the exhibition is occupied by a multitude of medical thinking and imagination, with their different cultural histories and understandings of where disease nests, what it is to be healed, what should be left untouched, and when to let go.

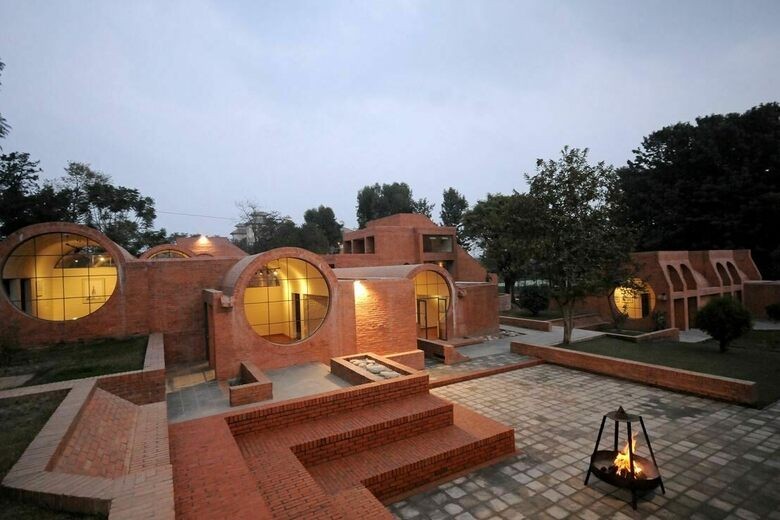

As you cross between Keshav Narayan Chowk and Sundari Chowk, through the museum’s beautiful ancient gardens, you are reminded of the Kathmandu Triennale 2077 exhibition at the Taragaon Museum. Just as medicine sees more than the inside of our bodies, and mapping the world draws both more and less than what really exists in the terrain, unseen by humans, gardens are themselves small visions of both a human organism and of the entire universe. Tending to a garden is akin to healing a body and to keeping a cosmic balance. But gardens were seen very differently across continents; implausible symmetric rows of calming but petty harmony; serene surfaces of water dividing the world in unreal halves; mountains and waterfalls and oceans no bigger than a gravesite; savagery hidden in a manor’s lawn; or gardens built by people who conquered their freedom after enslavement, summoning the landscapes of the home continent, with its crops, knowledge, and beauty